Lost Eden is a Saperavi blend, a grape native to Georgia which grew wild in its lush, verdant valleys for thousands of years. Taste Saperavi and you’ll notice the same fragrant, aromatic array found in mulberry, cherry, and blackberry. Distinct for its deep midnight-purple color that glows crimson in direct light, Lost Eden is smooth and silky with layers of black fruit that emerge as the flavor gains structure with age.

Currently available at these fine wine retailers with additional locations coming soon.

Wine.com

New Hampshire Wine and Liquor Outlet

Nashua (Willow Spring Plaza, Nashua)

294 DW Highway, Nashua, New Hampshire 03060

New Hampshire Wine & Liquor Outlet

Plaistow (Market Basket PLZ, Plaistow)

32 Plaistow Rd #2A, Plaistow, New Hampshire 03865

Lake Success Wine and Spirits

1560 Union Turnpike, New Hyde Park, NY 11040

516-216-5437

Total Wine Store 2201

1230 Old Country Rd, Westbury, NY 11590- US

516-357-0090

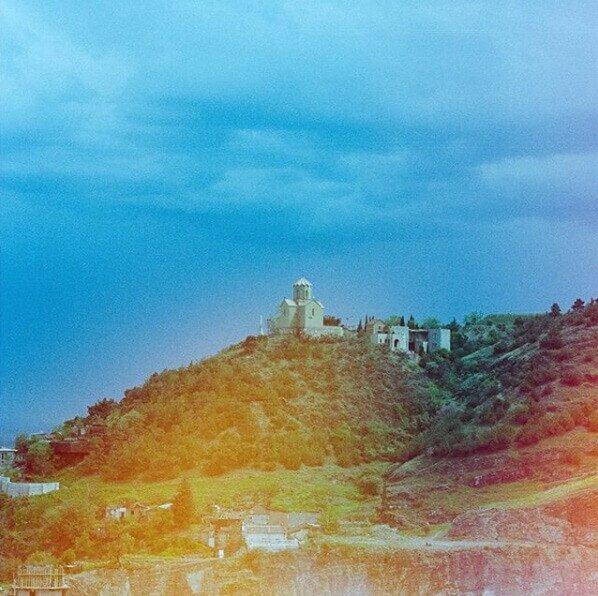

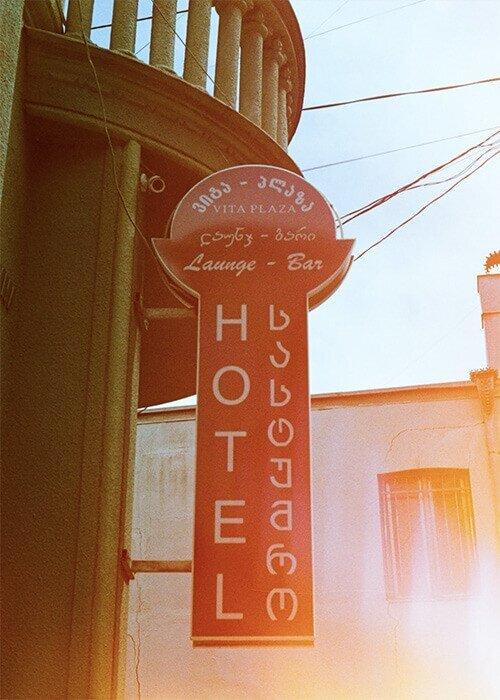

Wine is the most central and important part of Georgian culture. Anthropologists have traced the origins of winemaking back 8,000 years to a region just northwest of present-day Tbilisi. The land south of the Caucasus mountains is the true home of the first people on earth to conquer the grape.

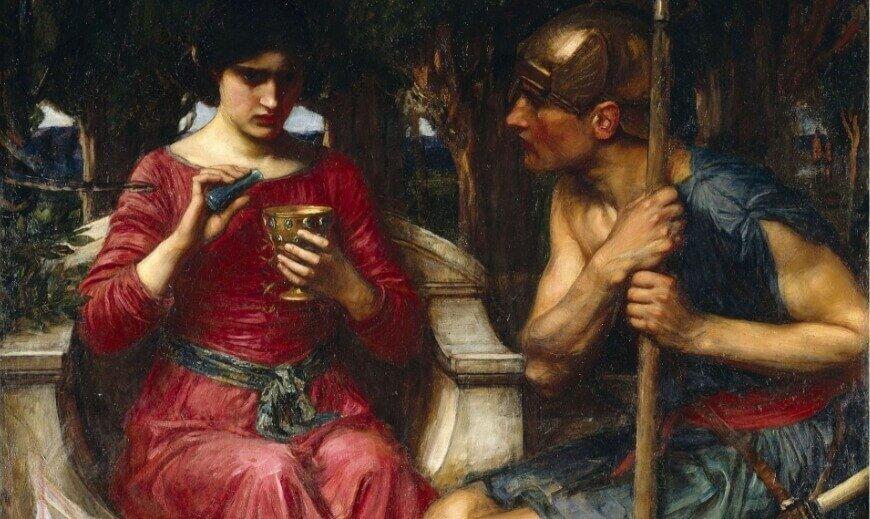

Winemaking in Georgia is an intimate, nationwide endeavor. It’s a craft infused with history, religion, and mythology, with hints of lore from the fourth century. An old legend tells of how soldiers prepared for battle by weaving a piece of grapevine into the breast of their armor. When they fell in battle, a vine would rise not just from their bodies but also their hearts.

Aspects of the ancient methods, which pre-date written history, are still applied to Georgian winemaking today. We use the same clay pot design and believe wine is better with less human intervention. So we harvest our grapes from arguably the oldest vines on Earth, place them deep underground in giant pots, called qvevris (pronounced kwevr-ees), and let time do its job.

There are 18 distinct wine-producing regions and Georgia is home to over 500 varieties of grape, which is more than anywhere else in the world. The very word “wine” is believed to have spread from the ancient Georgian word “Gvino” which means something that “rises, boils or ferments.” Recently, the qvevri technique itself was given heritage protection status by UNESCO. This is why the French regard Georgia as the “birthplace of wine.”

Wine is the most central and important part of Georgian culture. Anthropologists have traced the origins of winemaking back 8,000 years to a region just northwest of present-day Tbilisi. The land south of the Caucasus mountains is the true home of the first people on earth to conquer the grape.

Winemaking in Georgia is an intimate, nationwide endeavor. It’s a craft infused with history, religion, and mythology, with hints of lore from the fourth century. An old legend tells of how soldiers prepared for battle by weaving a piece of grapevine into the breast of their armor. When they fell in battle, a vine would rise not just from their bodies but also their hearts.

Aspects of the ancient methods, which pre-date written history, are still applied to Georgian winemaking today. We use the same clay pot design and believe wine is better with less human intervention. So we harvest our grapes from arguably the oldest vines on Earth, place them deep underground in giant pots, called qvevris (pronounced kwevr-ees), and let time do its job.

There are 18 distinct wine-producing regions and Georgia is home to over 500 varieties of grape, which is more than anywhere else in the world. The very word “wine” is believed to have spread from the ancient Georgian word “Gvino” which means something that “rises, boils or ferments.” Recently, the qvevri technique itself was given heritage protection status by UNESCO. This is why the French regard Georgia as the “birthplace of wine.”

TECHNOLOGY

TECHNOLOGY

winemaking technology that goes back over 8,000 years.